I will start out by apologizing for applying logic to any sort of history; particularly to the history of the production of blue cheeses. I also apologize for tempering history in order to do a good story. If it helps, I do believe what is to follow. By my readings, the timelines do seem correct. On the other hand, I am always amazed that the folks who invented and practiced writing seem to have invented just about everything else as well. That being said, it is my understanding that, in spite of 1500AD Italian writings to the contrary, Roquefort was indeed created before Gorgonzola.

So back we go to the adventures of our hunter/gatherer forefathers and foremothers: Our very-great-great grandfathers and grandmothers subsisted on what they could hunt and gather. Of course, that’s a bit of a generalization, because the men were largely the hunter types. They spent a lot of time away from the home because a hunter has to do what a hunter has to do. Herding was considered to be hunting as it included protecting the herd, not nursing children, and, let’s face it, getting out of the house. Part of this system kept the women-types at home, but in fact they also gathered. They gathered what they farmed and what was seasonally available in the nearby forest. More to the point (I’m getting there, I promise!), they gathered the milk from the nearby well-protected herds in order to supplement the hunters’ bounty. All this, mind you, while they birthed, nursed and reared the children. Well, somebody had to do it. So, the planning, preservation, and storing of the gathered foods so necessary for subsistence fell to the females while the guys were out hunting and protecting stuff.

Back to the milk. What the women did with it brings us to the cheeses: The most commonly produced cheese made from of the early long-preserved milk (aka, cheese) was feta-like. Basically a lightly acidic curdled curd – more or less like a firm ricotta – that was pressed, held and preserved in a brine that is twice the salinity of the Mediterranean. It was difficult to carry salt water inland, especially if you had not yet invented tanker trucks, but salt was (and still is) important to everything. Though refrigeration was still in the future, they had been taught by the Romans to build roads. The revolutionary solution was to get rid of the water and carry the salt inland to places like the small town of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon at the base of the massive cave-riddled Combalou Rock. (Take a look at it in the photo gallery. “Rock” seems like an understatement.)

In order to create the sheep’s-milk cheeses of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon and the blued cheese, first the milk had to be preserved. Sheep produce milk for six months of the year. The alternative to drinking it all at once (!) was to preserve it by making cheese. A lightly pressed, dry-salted, feta-like product. I am not going to belabor the process of making the cheese, as I have covered that already in my earlier articles, like this one, if you’re interested.

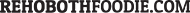

Next is storage: Good news! We got caves! Those caves maintain a constant temperature between 45F and 50F. But could there be bad news? There’s something in the cave that is turning our cheeses moldy! Nope, that's actually good news: That moldy old cheese was fed to an unsuspecting hunter, and not only did he not die in agony, he came back for more!

Finally, production: History has proven that we humans refine production by trial and error, eventually arriving at a desirable result (as far as we know, no hunters were harmed during this process). As the coincidental bluing of the stored cheeses became more desirable, the humans figured out how to duplicate and refine the bluing. To wit: If you put a piece of rye bread into the Combalou Caves and leave it there for a couple of weeks, it will be consumed by a fungus that we now call Penicillium Roqueforti. That fungus is crushed, mixed with the curds, and the magic happens! (Of course, before the 1850s it was all magic.) It eventually became a standard production practice to “needle” the cheeses, i.e., piercing the cheese to not only allow the dry salting to permeate, but also to invite the fungus inside to develop and spread. Which of those reasons for needling the cheese came first? Sorry, I missed that meeting. But it does explain the blue veins that travel through our favorite blues.

Are you wondering about how the salt made it inland? Those Roman-inspired roads that brought the salt from the Mediterranean to Roquefort-sur-Soulzon actually went two ways. (According to H.L. Mencken, one-way roads weren’t even invented until 1916. Really. Look it up.) So, along the road at a Mediterranean distribution point, the salt was paid for with this tasty blue cheese. Its fame eventually spread along the roads, old and new, far and wide. In the 1500s, the Italian city of Milan was along one of those roads (the old east/west line rather than the newer north/south stretch). Innovators that they were, they decided to make a copy of this blue-veined sheep’s milk legend. Out of cow’s milk, yet! The result was bigger, sweeter – altogether the same, but different. It was called Gorgonzola. It was wonderful and they wrote all about it.

Modern-day cheesemaking varies somewhat from the original methods. Some blue cheese formulas call for the mold to be mixed into the curds; others call for the traditional piercing of the curds with a needle to allow the mold to spread. Still others rely on naturally occurring mold spores in the air and let nature take its course. The general result is the same: A cheese with blue or green veins running through it, with flavors ranging from mild and creamy to downright pungent, even spicy. Food technologists have determined that this flavor signature is due to lipase enzymes produced by the mold. So what wines might stand up to this unique flavor? Wine Spectator makes reference to the classic matches, like Sauternes with Roquefort, and Port with Stilton. But what to do if you don't like dessert wines? Wine Spectator continues: If it's a strong blue, it needs a bigger wine, because blues can be both salty and strong. The wine should still be a little sweet, or at least fruity. In particular, the experts suggest Chardonnay and some Cabernet-based wines – especially fruity ones – for cow's milk blues. For sheep's milk cheeses, they suggest Cabernet-based wines and even Zinfandel. Interestingly, they shy away from table-wine pairings with goat’s milk blues. So you're on your own with the goats.

The delicious, azure-hued tendrils of this bluing process have spread throughout the world. In Spain it was created from the mixed milks of Cabrales. In England, those Brits did strange things to cow’s milk in the early 1700s and came up with Stilton. In nearby Pennsylvania, Sue Miller makes the wonderful Birchrun Hills Blue (http://www.birchrunhillsfarm.com/).

I eat them all, they make me happy, and when appropriate I ask for more. And to this day, not one cheesemonger has been harmed in the process.

Suggested reading: “Salt: A World History” by Mark Kurlansky. Very informative!